The Shape of Things to Come?

“The biblical fact,” Eugene Peterson points out in his book ‘Working the angles: the shape of pastoral integrity’, “is that there are no successful churches. There are, instead, communities of sinners, gathered before God week after week in towns and villages all over the world. The Holy Spirit gathers them and does his work in them. In these communities of sinners, one of the sinners is called pastor and given a designated responsibility in the community. The pastor’s responsibility is to keep the community attentive to God.” (1987:2)

The shape of training college programmes in the future may be many things; but a curriculum not fully dedicated to developing spirit filled leadership that maintains attentiveness to God, is a curriculum pulled out of shape. The Form of training was an important area for discussion for the European Training Leaders Network and followed on from the discussions of Essence, and then the Function of training. If the function of training is that of developing mature leaders capable of embracing the tension of innovation while maintaining the integrity of Salvation Army ministry, what do our colleges need to look like? What form should training curriculums take?

Spiritual Leadership

As contemporary leadership training is increasingly applied in the church context, to avoid growing confusion, a significant question is “what is a spiritual leader?” Spiritual leadership is more than being equipped with corporate motivational tools, in that it is a leadership that guides, feeds and nourishes; nurtures, heals and brings reconciliation, it is a leadership that steps out and away from a drive for efficiency and profit and the inner desires that seek relevance, popularity and power.

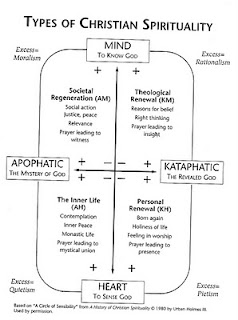

College training programmes require intentionality to appropriate a maturity of leadership that envisions and guides communities to attentiveness and responsiveness to what God is creating and doing. Urban Holmes in his book ‘Spirituality for Ministry’ identifies ‘the three D's’ that combine to create the right environment for this maturity, ‘Detachment’ from self; ‘Discretion’ of motivation; and ‘Discernment’ of action. The continued establishment of these right conditions for growth within training programmes is important if training programmes are to continue to function towards the training of mature integrated leaders.

The Dignity of Leadership

When considering the shape of things to come, the form of spiritual leadership training needs to embody the dignity of spiritual leadership. For that dignity to remain intact, through a sustained and meaningful ministry, there is a responsibility to build curricula that develops ‘thinking’ and not ‘thoughtless’ officers; that creates the right conditions for personal and spiritual maturity and also encourages engagement with kingdom centred mission.

This dignity reflects the thinking of Catherine Booth’s sentiment for heart, head and hand training or as I heard Moltmann once acknowledge, the need for orthodoxy (right thinking), orthopathy (right being) and orthopraxy (right doing). Cadet lecture notes from 1940 would indicate that this is not particularly new, with the most important part of training seen as the formation of ‘personal religion and character’ in terms of spiritual experience, necessary education and actual work on the field. The need remains the same for Salvation Army spiritual leaders mature in their being, thinking and doing.

Maturity of Thinking (Orthodoxy)

Cadets in 1940 were warned, “you must be at least up to the level of the people to whom you will go: you cannot teach others unless you yourselves are taught”. This sentiment would seem foundational in the work of Grenz and Olsen who, in their book ‘Who needs theology? An invitation to the study of God’, identify a spectrum of theological thinking, as minds organise thoughts and beliefs. Training has a responsibility to nurture a learning environment that encourages a move away from lazy and clichéd theological thought, to coherence that will contribute to a sustained and meaningful ministry. Grenz and Olsen identify, as a necessary part of any maturing thought process, the need to: “…identify and expunge blatant contradictions, and make sure that there are good reasons for interpreting Christian faith in the way we do"(pp25).

Maturity of Being (Orthopathy)

Spiritual leaders need a strong sense of self, not only in terms of personality but also in terms of what is termed Faith Development. Fowler in his landmark book Stages of Faith illustrates the various milestones an individual will encounter as they mature in faith. The recognition that spirituality matures, has long been recognised as an important area of spiritual direction, and represents a stream of consciousness reflective of the process of coming to wholeness which reaches back to the Cappadocian’s and early church fathers.

The maturing of faith represents what Fowler suggests is a dynamic progression and way of living, rather than merely something you have or do not have. The development of faith is discovering union with God and encountering what it is to be fully human living in the design and plan of God. Throughout his book ‘Chrysalis’ Alan Jamieson points out that this maturing of our faith is a process through which we are ‘fashioned, shaped and prepared for use' as the instruments in the purposes of God. Mature leaders are inspired; their perception of self reflects their understanding of what it is, through the Holy Spirit, to not only grow into the fullness of Christ, but also identify that which ‘hinders’.

Maturity of Doing (Orthopraxy)

The dignity of leadership is complete with a maturity of doing as spiritual leaders incarnate or embody God’s purposes in mission. A mature understanding of mission is therefore an inevitable requirement of the spiritual leader whose ministry is to be meaningful and sustained. A maturity of doing moves away from potential dualistic thinking, and will focus on Jesus as the means of understanding a Trinitarian model of mission. Any suggestion that loving God is spiritual, while loving neighbours is material is undermined; the false dichotomy that fractures the Great Command is closed to make sense of the Great Commission. A mature orthopraxy will embrace Jesus’ comprehensive missional message, motive and life through a complete recognition and agreement with Lesslie Newbigin that “we are not authorised to do it any other way.”

Maturity in mission not only needs initial ascent of thought and action that engages with the breadth of missional theology; but it also requires ongoing theological reflection that maintains the primacy of Christ’s mission through the church in God’s world. Reflective leaders are able to use tools of theological reflection to identify where mission is being pulled out of shape, in other words where mission stops being Christ shaped.

Conclusion

This series looking at the ‘essence, function and form’ of training has covered much ground. From the discussion of essence and the challenge to embrace and facilitate a creative tension; through an exploration of expectations and the acknowledgement that function flows from essence not form. It is from here that this discussion of form, or the shape, of training college programmes has emerged.

Training colleges need to be shaped to develop leaders who demonstrate good emotional health through knowing ‘who and whose they are’; training colleges need to be shaped to develop thinking and not thoughtless leaders and finally training colleges need to be shaped to develop a maturity of leadership that culminates in action with missional clarity. This is Chrysostom’s one thing that counts, ‘excellence of character’, and this is what Catherine Booth gets us to think about when she asks:

“What does God want with us? He wants us just to be, and to do. He wants us to be like His Son, and then to do as His Son did; and when we come to that He will shake the world through us”

The shape of training college programmes in the future may be many things; but a curriculum not fully dedicated to developing spirit filled leadership that maintains attentiveness to God, is a curriculum pulled out of shape. The Form of training was an important area for discussion for the European Training Leaders Network and followed on from the discussions of Essence, and then the Function of training. If the function of training is that of developing mature leaders capable of embracing the tension of innovation while maintaining the integrity of Salvation Army ministry, what do our colleges need to look like? What form should training curriculums take?

Spiritual Leadership

As contemporary leadership training is increasingly applied in the church context, to avoid growing confusion, a significant question is “what is a spiritual leader?” Spiritual leadership is more than being equipped with corporate motivational tools, in that it is a leadership that guides, feeds and nourishes; nurtures, heals and brings reconciliation, it is a leadership that steps out and away from a drive for efficiency and profit and the inner desires that seek relevance, popularity and power.

College training programmes require intentionality to appropriate a maturity of leadership that envisions and guides communities to attentiveness and responsiveness to what God is creating and doing. Urban Holmes in his book ‘Spirituality for Ministry’ identifies ‘the three D's’ that combine to create the right environment for this maturity, ‘Detachment’ from self; ‘Discretion’ of motivation; and ‘Discernment’ of action. The continued establishment of these right conditions for growth within training programmes is important if training programmes are to continue to function towards the training of mature integrated leaders.

The Dignity of Leadership

When considering the shape of things to come, the form of spiritual leadership training needs to embody the dignity of spiritual leadership. For that dignity to remain intact, through a sustained and meaningful ministry, there is a responsibility to build curricula that develops ‘thinking’ and not ‘thoughtless’ officers; that creates the right conditions for personal and spiritual maturity and also encourages engagement with kingdom centred mission.

This dignity reflects the thinking of Catherine Booth’s sentiment for heart, head and hand training or as I heard Moltmann once acknowledge, the need for orthodoxy (right thinking), orthopathy (right being) and orthopraxy (right doing). Cadet lecture notes from 1940 would indicate that this is not particularly new, with the most important part of training seen as the formation of ‘personal religion and character’ in terms of spiritual experience, necessary education and actual work on the field. The need remains the same for Salvation Army spiritual leaders mature in their being, thinking and doing.

Maturity of Thinking (Orthodoxy)

Cadets in 1940 were warned, “you must be at least up to the level of the people to whom you will go: you cannot teach others unless you yourselves are taught”. This sentiment would seem foundational in the work of Grenz and Olsen who, in their book ‘Who needs theology? An invitation to the study of God’, identify a spectrum of theological thinking, as minds organise thoughts and beliefs. Training has a responsibility to nurture a learning environment that encourages a move away from lazy and clichéd theological thought, to coherence that will contribute to a sustained and meaningful ministry. Grenz and Olsen identify, as a necessary part of any maturing thought process, the need to: “…identify and expunge blatant contradictions, and make sure that there are good reasons for interpreting Christian faith in the way we do"(pp25).

Maturity of Being (Orthopathy)

Spiritual leaders need a strong sense of self, not only in terms of personality but also in terms of what is termed Faith Development. Fowler in his landmark book Stages of Faith illustrates the various milestones an individual will encounter as they mature in faith. The recognition that spirituality matures, has long been recognised as an important area of spiritual direction, and represents a stream of consciousness reflective of the process of coming to wholeness which reaches back to the Cappadocian’s and early church fathers.

The maturing of faith represents what Fowler suggests is a dynamic progression and way of living, rather than merely something you have or do not have. The development of faith is discovering union with God and encountering what it is to be fully human living in the design and plan of God. Throughout his book ‘Chrysalis’ Alan Jamieson points out that this maturing of our faith is a process through which we are ‘fashioned, shaped and prepared for use' as the instruments in the purposes of God. Mature leaders are inspired; their perception of self reflects their understanding of what it is, through the Holy Spirit, to not only grow into the fullness of Christ, but also identify that which ‘hinders’.

Maturity of Doing (Orthopraxy)

The dignity of leadership is complete with a maturity of doing as spiritual leaders incarnate or embody God’s purposes in mission. A mature understanding of mission is therefore an inevitable requirement of the spiritual leader whose ministry is to be meaningful and sustained. A maturity of doing moves away from potential dualistic thinking, and will focus on Jesus as the means of understanding a Trinitarian model of mission. Any suggestion that loving God is spiritual, while loving neighbours is material is undermined; the false dichotomy that fractures the Great Command is closed to make sense of the Great Commission. A mature orthopraxy will embrace Jesus’ comprehensive missional message, motive and life through a complete recognition and agreement with Lesslie Newbigin that “we are not authorised to do it any other way.”

Maturity in mission not only needs initial ascent of thought and action that engages with the breadth of missional theology; but it also requires ongoing theological reflection that maintains the primacy of Christ’s mission through the church in God’s world. Reflective leaders are able to use tools of theological reflection to identify where mission is being pulled out of shape, in other words where mission stops being Christ shaped.

Conclusion

This series looking at the ‘essence, function and form’ of training has covered much ground. From the discussion of essence and the challenge to embrace and facilitate a creative tension; through an exploration of expectations and the acknowledgement that function flows from essence not form. It is from here that this discussion of form, or the shape, of training college programmes has emerged.

Training colleges need to be shaped to develop leaders who demonstrate good emotional health through knowing ‘who and whose they are’; training colleges need to be shaped to develop thinking and not thoughtless leaders and finally training colleges need to be shaped to develop a maturity of leadership that culminates in action with missional clarity. This is Chrysostom’s one thing that counts, ‘excellence of character’, and this is what Catherine Booth gets us to think about when she asks:

“What does God want with us? He wants us just to be, and to do. He wants us to be like His Son, and then to do as His Son did; and when we come to that He will shake the world through us”

Comments

Enjoyed the read - and agree with what you are say. Not sure if I passed it on or not but the is an article that can be downloaded:

What is Pastoral Leadership? Roland G Kuhl, that worth the read. He is challenging the term "leader" as an appropriate metaphor for the church.

Retirement has been great to date - have just taught a unit at College on Gospels and Mission, which went well. Wayne